HRT and SERMs: New Guidelines for Patient Management - Part 1

Chairperson: Thomas E. Nolan, MD, MBA; Faculty: Robin K. Dore, MD; Lori Mosca,

MD, MPH, PhD; Jane Cauley, DrPH; Susan Johnson, MD

Editorial Content produced by the Annenberg Center for Health Sciences.

Copyright © 2003 Quadrant HealthCom Inc.

This CME activity, "HRT and SERMs: New Guidelines for

Patient Management," was originally offered as a supplement to the March

2002 Special Edition to The Female Patient, certified for CME. The original

supplement was published prior to the early termination of the estrogen/progestin

arm of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial in July 2002 due to adverse

outcomes. The companion estrogen-alone trial continues, with close monitoring

by the data and safety monitoring board. The Women's International Study on

long Duration Oestrogen after Menopause (WISDOM) trial was halted in October

2002 because the main funding body of WISDOM, the Medical Research Council

(UK), withdrew funding for the study. More recent references discussing trial

outcomes have been added below, and are recommended reading for completion of

this CME activity.

Faculty

affiliations and disclosures are at the end of

this activity.

Release Date: March 31, 2003; Valid for

credit through March 31, 2004

Target Audience

This activity was developed for OB/GYNs and primary care physicians.

Goal

Information on estrogen replacement is rapidly becoming available. At the

same time, practitioners suggest the information is not always clear. This

piece will clarify what is now known about HRT and SERMs, as well as where

the field may be heading.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this educational activity, participants should be able

to:

- Create a treatment plan for the prevention of osteoporosis.

- Describe the effects of cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal

women.

- Discuss gynecologic considerations in postmenopausal women.

- Discuss breast cancer and SERMs.

Credits Available

Physicians - up to 2.0 AMA PRA category 1 credit(s)

All other healthcare professionals completing continuing education

credit for this activity will be issued a certificate of participation.

Participants should claim only the number of hours actually spent in

completing the educational activity.

Canadian physicians please note:

Medscape's CME activities are eligible to be submitted for either

Section 2 or Section 4 [when creating a personal learning project] in

the Maintenance of Certification program of the Royal College of

Physicians and Surgeons, Canada [RCPSC]. For details, go to www.mainport.org.

Accreditation Statements

For Physicians

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with

Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for

Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of

The Annenberg Center for Health Sciences at Eisenhower and Medscape,

Inc. The Annenberg Center is accredited by the Accreditation Council

for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical

education for physicians.

The Annenberg Center for Health Sciences designates this

educational activity for a maximum of 2.0 hours in category 1 credit

toward the AMA Physician's Recognition Award. Each physician should

claim only those hours of credit that he/she actually spent in the

educational activity.

This activity consists of a website. Successful completion is achieved

by reading the material, reflecting on its implications in your

practice, and completing the assessment component.

The estimated time to complete the activity is 2 hours.

For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the

accredited provider for this CME/CE activity:

mpederson@annenberg.net.

For technical assistance, contact

CME@webmd.net.

Instructions for Participation and Credit

This online, self-study activity is formatted to include text,

graphics, and may include other multi-media features.

Participation in this self-study activity should be completed in

approximately 2.0 hours. To successfully complete this activity and

receive credit, participants must follow these steps during the period

from March 31, 2003 through March 31, 2004.

- Make sure you have provided your professional degree in your

profile. Your degree is required in order for you to be issued the

appropriate credit. If you haven't, click

here. For information on applicability and acceptance of

continuing education credit for this activity, please consult your

professional licensing board.

- Read the target audience, learning objectives, and author

disclosures.

- Study the educational activity online or printed out.

- Read, complete, and submit answers to the post test questions and

evaluation questions online. Participants must receive a test score

of at least 70%, and respond to all evaluation questions to receive

a certificate.

- When finished, click "submit."

- After submitting the activity evaluation, you may access your

online certificate by selecting "View/Print Certificate"

on the screen. You may print the certificate, but you cannot alter

the certificate. Your credits will be tallied in the CME Tracker.

This activity is supported by an educational grant from Eli Lilly.

Legal Disclaimer

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of Medscape,

The Annenberg Center for Health Sciences, the companies providing educational

grants or the authors and writers. These materials may discuss uses and

dosages for therapeutic products that have not been approved by the United

States Food and Drug Administration. All readers and continuing education

participants should verify all information and consult a qualified healthcare

professional before treating patients or utilizing any therapeutic product

discussed in this educational activity.

Contents of This CME Activity

- The Role of HRT and

SERMs: Evidence-Based Medicine

Introduction

An Ideal Time for Options

Looking Ahead

References

- Osteoporosis:

Fractures and Key Risk Factors

A Global Health Issue

Osteoporosis Redefined

Risk Factors

Morbidity and Mortality

Identifying Risks

Treatment and Fracture Risk Reduction

Ongoing Studies

What's Next?

Conclusion

References

- Cardiovascular

Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Introduction

Markers of CVD Risk

The Role of HRT in CVD

New HRT Guidelines

Updated Cholesterol Management Guidelines

Use of Statins and SERMs

Conclusion

References

- The Faculty

Speaks: A Roundtable Discussion on Postmenopausal Health Care

Cardiovascular Health

Bone Degeneration

Safety of Postmenopausal Interventions

Conclusion

References

HRT and SERMs: New Guidelines for Patient Management - Part 1

The Role of HRT and SERMs: Evidence-Based Medicine

Thomas E. Nolan, MD, MBA

Introduction

The time for this program has never been better: Researchers are intensely

exploring the role of female hormones in the development of age-related

illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and cancer. Such

investigation has unveiled estrogen's benefits in preserving bone mineral

density (BMD) and preventing certain gynecologic cancers, and has provided

evidence that combined estrogen and progesterone exert positive effects on

serum lipid levels and, quite possibly, the risk of coronary artery disease.

This investigation has also unveiled much controversy, which has complicated

prevention and treatment protocols.

As diligent as many healthcare providers have been in communicating to

patients about the various advantages of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT)

and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), many postmenopausal women have been

less enthusiastic about long-term use of these interventions. Although the

many benefits of supplemental estrogen have been documented in numerous

studies, several factors contribute to many patients' lack of interest in and

compliance with ERT and HRT. These include real and perceived breast

tenderness, weight gain, and skin changes, as well as the possible risks of

breast and ovarian cancer.

The Role of HRT and SERMs: Evidence-Based Medicine

Thomas E. Nolan, MD, MBA

An Ideal Time for Options

Because of these limitations on ERT and HRT, a great emphasis has been

placed on identifying estrogen-related therapies that postmenopausal women

might perceive as less fraught with side effects and risks. These efforts have

yielded selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs): compounds that act

efficiently through the estrogen receptor but do not increase the amount of

active hormone in the body. The first agent observed to act in this manner was

tamoxifen, used for the prevention of breast cancer in women at high risk for

the disease. Tamoxifen has also been widely observed to exert beneficial

effects on bone,[1] and, more recently, markers for cardiovascular

health.[2] However, tamoxifen has also been shown to incur some

risk of ocular disorders and uterine cancer.[3,4]

Further efforts to improve upon the prevention of age-related disease in

postmenopausal women have led to the development of another SERM, raloxifene,

designed for even higher selectivity in this population. Raloxifene is

currently under investigation for the prevention of breast cancer and may

actually hold promise in several therapeutic areas. Readers should note,

however, that the risk of thromboembolism is the same in women using

raloxifene as in those using exogenous estrogen, and identification of

appropriate disease markers in at-risk patients is warranted. The areas in

which SERMs are being explored for optimum benefit were discussed in a

roundtable meeting entitled "HRT and SERMs: Evidence-Based Data to Guide

Patient Management," the proceeds of which are presented here in the form

of clinical articles and an additional dialogue section titled "The

Faculty Speaks." Brief summaries of the clinical articles appear below.

Skeletal Activity.

Raloxifene decreases bone turnover in a manner similar to that seen with

estrogen replacement. As discussed in the article, "Osteoporosis:

Fractures and Key Risk Factors" by Robin K. Dore, MD, this agent has been

extensively studied for its use in reducing osteoporotic fracture in the

spine, hip, and total body.

Applications in Heart Health.

As cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number-one killer of women (and

men), healthcare providers are generally enthusiastic about the discovery of

cardiovascular benefits in a new drug. Currently, there is good reason to

believe that the SERMs offer some consistent and positive effects on

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, without increasing serum triglycerides or

decreasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.[2] The article,

"Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the

Threat," by Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD, provides thoughtful insight into

these and other therapies to reduce the incidence of CVD among older women.

The Role of HRT and SERMs: Evidence-Based Medicine

Thomas E. Nolan, MD, MBA

Looking Ahead

SERMs represent a very exciting option for disease prevention in certain

postmenopausal women. In enthusiastic response to our readers, the articles in

this program aim to "cut through the noise" that too often clouds

the issue of postmenopausal hormone-related therapy. It is my hope that you,

the reader, will be able to draw from the insights published here to enhance

the overall well-being of our postmenopausal patient population.

The Role of HRT and SERMs: Evidence-Based Medicine

Thomas E. Nolan, MD, MBA

References

- Powles TJ, Hickish T, Kanis JA, Tidy A, Ashley S. Effect of tamoxifen on

bone mineral density measured by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in

healthy premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol.

1996;14(1):78-84.

- Love RR, Wiebe DA, Feyzi JM, Newcomb PA, Chappell RJ. Effects of

tamoxifen on cardiovascular risk factors in postmenopausal women after 5

years of treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994; 86:1534-1539.

- Nayfield SG, Gorin MB. Tamoxifen associated eye disease: a review. J

Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):1018-1026.

- Dessole S, Cherchi PL, Ruiu GA, et al. Uterine metastases from breast

cancer in a patient under tamoxifen therapy: case report. Eur J Gynaecol

Oncol. 1999;20(5-6):416-417.

- Cauley JA, Norton L, Lippman ME, et al. Continued breast cancer risk

reduction in postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene: 4-year results

from the MORE trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;65(2):125-134.

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

A Global Health Issue

Osteoporosis is a global public health problem associated with aging, but

it is not an inevitable part of aging. Its diagnosis should be considered in

all women who have had fractures as adults.

The United States, blessed with an aging population, has the dubious

distinction of being a world leader in fractures caused by this disease.[1]

Recognizing that osteoporosis and fractures are largely preventable, the

National Institutes of Health (NIH) convened an NIH Development Consensus

Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy in March 2000 to

address what it perceived as a "major health threat" affecting 28

million Americans, 80% of them women.[2] (Table 1) Among other

issues, the panel was asked to discuss the meaning of osteoporosis, the

consequences of this disease, and the optimal evaluation and treatment of

osteoporosis and fractures. Given the NIH view that osteoporosis is largely

preventable and frequently not diagnosed, even after a fracture has occurred,

it is not surprising that the panel concluded: "There is a need to

determine the most effective method of educating healthcare professionals and

the public about the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of

osteoporosis."[2] It is hoped that this article will be a

helpful step in that direction.

Table 1. Osteoporosis Statistics

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

Osteoporosis Redefined

For many years, osteoporosis was viewed simply as a fracture: the outcome

of a "silent" process that was not well understood. While the

complex process leading to an excess of bone resorption over bone formation

remains asymptomatic, major advances have been made in the understanding of

the basic science underlying this process[3,4] and the biomechanics

of fracture.[5]

Osteoporosis is now defined as a skeletal disorder characterized by

compromised bone strength, which predisposes the patient to an increased risk

of fracture.[2] The elements of bone strength are bone density and

bone quality. Bone density, as measured by bone densitometry, is expressed as

grams of mineral per area and the patient's bone density is compared with a

young adult peak bone mass value (called a T-score). Bone quality includes

bone architecture, turnover, damage accumulation (eg, microfractures), and

mineralization. A fracture is the outcome of the application of

failure-inducing force to strength-compromised, or osteoporotic, bone.[2]

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

Risk Factors

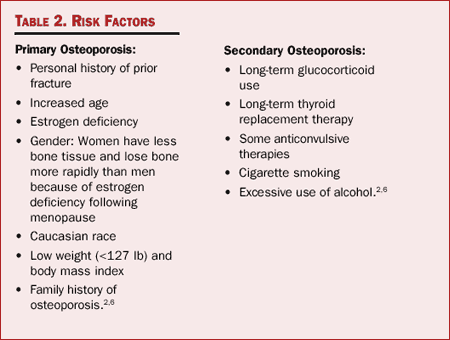

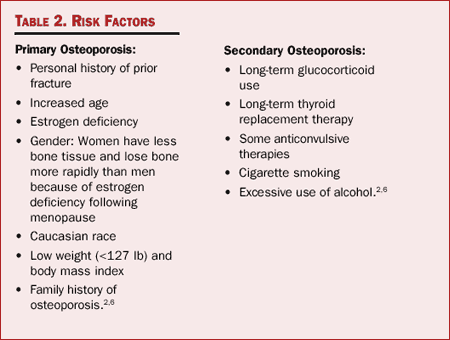

Osteoporosis can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary

osteoporosis most often occurs in postmenopausal women and older men, although

it can occur at any age. Secondary osteoporosis is a result of medications,

other conditions, or diseases. Risk factors for primary and secondary

osteoporosis are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Risk Factors

While osteoporosis may be a silent disease, it is striking that the most

important risk factors are apparent from a brief look at a patient and his or

her chart. It is also apparent that ancillary medical personnel, and even the

patient, can perform a rudimentary risk assessment. It is therefore essential

to ensure that the osteoporosis "radar" is on as healthcare

providers go about their daily clinical practice.

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

Morbidity and Mortality

Osteoporosis and associated fractures are a major public health concern

because of the cost, disability, decreased quality of life, and increased

mortality associated with fractures.

Hip Fractures.

Hip fractures have traditionally been the focus of osteoporosis because

they are easy to diagnose and result in costly hospitalizations and nursing

home placements that are easy to quantify. In addition, there is a 10% to 20%

excess mortality in the 6 months following a hip fracture. For those who

survive, the picture is not encouraging: One year after a hip fracture, 40% of

patients are still unable to walk unassisted, 60% have difficulty with at

least one essential activity of daily living, and 80% are restricted in other

activities, such as driving and shopping for groceries.[7] Nearly

one third of patients with hip fractures enter nursing homes within the year

following a fracture.[2]

Given the morbidity and mortality associated with hip fracture, it is

important to remember that a very effective way to prevent a hip fracture in a

given population may be to utilize hip protectors.[8]

Hip fractures usually occur when women are in their late 70s and 80s.[2]

This is not surprising, because 50% of women in their 80s have osteoporosis

(as measured by bone density studies) at one or both hips, a reflection of the

impact of aging on bones.[9]

Vertebral Fractures.

A key insight of the NIH Consensus Panel was that, while a great deal is

known about the impact of hip fractures, the adverse effects of vertebral

fractures on health, function, and quality of life are often underestimated.

Vertebral fractures lead to chronic pain and disability.[2] They

can result in height loss and kyphosis, with associated postural and height

changes that erode self-esteem. Compression of the thoracic and abdominal

cavities results from multiple vertebral fractures. Multiple thoracic

fractures may result in restrictive lung disease, and lumbar fractures may

alter abdominal anatomy, leading to constipation, abdominal pain, distention,

reduced appetite, and premature satiety.[10-12]

Vertebral fractures are also associated with an increase in mortality. In a

population-based study of survival following osteoporotic fracture, Cooper and

colleagues examined the survival rate of 335 patients who had initial

radiologic diagnoses of vertebral fracture between 1985 and 1989 and compared

them to survival rates of patients who had experienced hip fractures.[13]

They found that, while there was a much greater incidence of mortality among

hip fracture patients within the first 6 months, the estimated survival rates

at 5 years after diagnosis were comparable. Patients with vertebral fractures,

however, had a worse survival rate than expected; that rate diverged steadily

from expected values throughout the course of the study.

Kado and associates found an increased risk of death of 1.23 in patients

who had experienced one or more vertebral fractures.[14] In the

case of severe vertebral fractures, the increased risk of death was 1.34, and

there was an increased risk of death related to respiratory disorders as well.

This study demonstrated that vertebral fractures contribute to comorbid

conditions, such as pneumonia as the result of incomplete lung expansion, and

consequently to mortality.

Cauley and colleagues examined the relative risks of dying following a

clinically related fracture that was apparent to the examining physician, as

reported in the Fracture Intervention Trial.[15] The relative risk

of death following any clinical fracture was 2.15. After a hip fracture, the

risk was 6.68, but after a clinical vertebral fracture, the risk rose to 8.64

-- the highest risk associated with any clinical fractures.

Vertebral fractures are a bearer of bad tidings for the skeleton. They may

reflect generalized loss of bone strength and increase the force on other

vertebral bodies, making them more likely to fail. They may also weaken

muscles, cause pain, and/or upset balance and thereby increase the risk of a

fall. It is not surprising that there is an increased risk of subsequent

fractures following an initial vertebral fracture.

In a study that was conducted to determine whether vertebral fractures

predict subsequent fractures, the authors found that not only do vertebral

fractures indicate an increased risk for subsequent fractures, but that the

greatest risk of subsequent fracture was in the axial skeleton.[16]

After an initial vertebral fracture, the authors observed a 12.6-fold increase

in additional vertebral fractures, a 2.3-fold increase in hip fractures, and a

1.6-fold increase in additional forearm fractures.

A study by Lindsay and associates analyzed data from four large 3-year

osteoporosis treatment trials conducted at 373 study centers in the United

States and abroad.[17] Subjects were a mean age of 74 years, had a

mean of 28 years since menopause, and were known to have had one or more

vertebral fractures. Data analysis showed that patients who had one or more

vertebral fractures at baseline had a 5-fold increased risk of having a

fracture during the first 12 months of the study. Among patients who developed

a vertebral fracture during the study, approximately 20% had a new vertebral

fracture in the next 12 months.

Not every aging woman will develop vertebral fractures, but they are very

common and underdiagnosed. If healthcare providers can prevent a vertebral

fracture, then prevention of the morbidity and mortality associated with that

fracture and the prevention of hip and other fractures may be achieved as

well.

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

Identifying Risks

The National Institutes of Health Consensus Panel regards the assessment of

bone mass, identification of fracture risk, and determination of who should be

treated as the optimal goals when evaluating patients for osteoporosis.[2]

Until the late 1980s, it was difficult to identify the patients who were at

risk for a fracture before it occurred. Since that time, bone mineral density

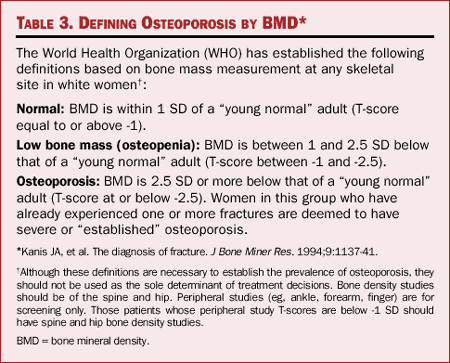

(BMD) measurements have become fairly common. While BMD is not a true

measurement of bone strength, it is the best surrogate measurement available

at present.

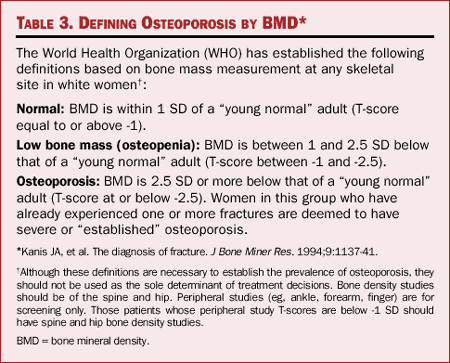

Table 3. Defining Osteoporosis by BMD

The World Health Organization (WHO) operationally defines osteoporosis as

bone density 2.5 SD below the mean for young white adult women (Table 3).

Clinicians now use risk factors to help determine which patients should be

evaluated for osteoporosis with a bone density test. Several important risk

factors for osteoporosis have been identified; however, the list can be

expanded to include the following:

- Adults with vertebral, rib, hip, or distal forearm fractures should be

evaluated for the presence of osteoporosis. The National Osteoporosis

Foundation (NOF) recommends that any woman who has had a fracture as an

adult be evaluated for osteoporosis.[18]

- Since osteoporosis increases with age, the NOF recommends that every

woman aged 65 years and older have a bone density test.[18]

- Corticosteroid (glucocorticoid) use is the major cause of secondary

osteoporosis.

- Estrogen deficiency leads to osteoporosis, particularly in women who

experience rapid bone loss following menopause or who have early menopause

(ie, before age 40). Women with irregular periods prior to menopause may

have osteoporosis due to estrogen deficiency. Also, female athletes who

don't have regular menstrual periods may have osteoporosis at an early

age, particularly if this behavior is accompanied by an eating disorder.

The NOF recommends that every woman aged 65 years and older have a bone

density test.

- Family history is very important, and should include both the mother's

and the father's side of the family. The genetic tendency to develop

osteoporosis is not exclusive to the female's side of the family, nor is

it exclusively a female tendency. Patients who are diagnosed with

osteoporosis should be encouraged to talk to their brothers and sons about

osteoporosis screening and treatment.

- Older patients who lose a significant amount of body weight (ie, 5%) are

at risk for bone mass loss as well.[19]

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

Treatment and Fracture Risk Reduction

A patient who has been diagnosed with osteoporosis should be treated

promptly and aggressively. The NOF recommends initiating therapy to reduce

fracture risk in women with BMD T-scores below -2.0 SD in the absence of risk

factors and in women with T-scores below -1.5 SD if other risk factors are

present. Women aged older than 70 years and who have multiple risk factors

(especially those with previous fractures) are at enough of a risk for

fracture to begin treatment without BMD testing.[18]

Several options for prevention or treatment of osteoporosis are available,

including therapies that enhance bone mass and reduce risk of fractures. All

current options are antiresorptive therapies: They inhibit bone resorption by

osteoclasts.

Hormone Replacement.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is indicated for the prevention of

osteoporosis. Several short-term studies and a few longer-term studies using

BMD as the primary outcome have shown significant efficacy. For example, the

Postmenopausal Estrogen/ Progestin Interventions (PEPI) trial showed that HRT

increases bone density in the spine and the hip and produces a reduction in

bone turnover.[20] There have not, however, been any large,

randomized, controlled clinical trials showing fracture reduction with HRT.

The Women's Health Initiative (initiated in 1992, with a planned completion

date of 2007[21]) may show that HRT prevents fractures, but at the

present time, no data are available. As HRT may be associated with a modest

increase in the risk of breast cancer with long-term use and is associated

with increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), the clinician is advised to

seek alternative treatments for women diagnosed with or at risk for

osteoporosis who also have a history of, or at significant risk for, breast

cancer or DVT. HRT may have significant side effects in some individuals,

including vaginal bleeding, breast tenderness, mood disturbances,[18]

and gallbladder disease.[17]

SERMs.

The NIH Consensus Panel considered the development of selective estrogen

receptor modulators (SERMs) "an important new thrust in osteoporosis

research."[2] The interest in developing a SERM for the

prevention and treatment of osteoporosis was driven by the observation that

tamoxifen, an effective adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, has estrogen-like

effects on bone.[22]

The SERM raloxifene, approved for the prevention of postmenopausal

osteoporosis in 1997 and the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in 1999,

has estrogen-like effects on bone, but acts as an estrogen antagonist on

breast and endometrial tissue.[23]

Raloxifene has been shown to prevent bone loss at the spine, hip, and total

body.[23] More importantly, the 3-year randomized Multiple Outcomes

of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial demonstrated that raloxifene

significantly reduced the risks of vertebral fracture. At 1 year, therapy with

raloxifene resulted in a 68% reduction in clinical vertebral fractures. At 3

years, raloxifene decreased vertebral fractures in women who had not had

fractures at baseline by 55%. In women who had vertebral fractures entering

the trial, raloxifene produced a 30% reduction.[24] The MORE trial

was continued into a fourth year, but because the data had not been analyzed

and the significance of the reduction in vertebral fractures was not known at

that point, women who continued the trial into the fourth year were allowed to

add a bone-active agent, with the exception of estrogen. The investigators and

participants remained blinded as to whether patients were taking raloxifene or

placebo. At 4 years, raloxifene continued to provide fracture protection for a

significant number of women. Among women who had no fractures at the start of

the study 4 years earlier, raloxifene produced a 49% reduction in vertebral

fractures. In the cohort with existing vertebral fractures at study entry,

there was a 34% reduction.[25]

Raloxifene increases the risk of DVT to a degree similar to that observed

with estrogen. In addition, an increase in hot flashes is observed

(approximately 6% more than with placebo). Thus, raloxifene should not be used

to treat menopausal symptoms.[18] However, for asymptomatic women

who were taking estrogen for menopausal symptoms and wish to remain on

preventive therapy, it is reasonable to change their therapy to raloxifene.

Calcitonin.

Salmon calcitonin is a synthetic hormone that inhibits bone resorption and

is approved for the treatment of osteoporosis in women 5 years after menopause

has occurred. It is available as an intranasal spray; a single daily dose

provides 200 units (u) of the drug. In a 5-year, double-blind, randomized,

placebo-controlled trial of 511 postmenopausal women with established

osteoporosis, participants were randomized to receive 100, 200, or 400 u of

intranasal calcitonin daily.[26] Results showed that only the 200-u

dose produced a significant (36%) reduction of vertebral fractures, with no

reduction in hip fractures and no significant change in either bone density or

bone turnover.

Bisphosphonates.

Alendronate sodium was the first bisphosphonate approved for use in

osteoporosis. Alendronate 5 mg daily and 35 mg once weekly are approved by the

US Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of osteoporosis. The dose

for the treatment indication is 10 mg daily or 70 mg once weekly. Alendronate

is also approved for the treatment of bone loss in both men and women as a

result of prolonged glucocorticoid use and for the treatment of male

osteoporosis.[18] Large, randomized, controlled trials have shown

that alendronate reduces the incidence of fracture at the spine, hip, and

wrist by 50% in patients with osteoporosis.[27]

Alendronate must be taken on an empty stomach, first thing in the morning,

at least 30 minutes before having any food or beverage. It must be taken with

a large glass of water, and patients are advised to sit upright or stand for

30 minutes after administration. In clinical trials, the incidence of side

effects with alendronate was no different than placebo; however, in clinical

experience, upper gastrointestinal disturbance, particularly esophageal

symptoms (eg, chest pain, heartburn, painful or difficult swallowing) has been

a problem with alendronate in some patients. A rare (probably <1%) reported

complication of alendronate is esophageal ulceration.[18]

Risedronate is a second bisphosphonate approved for use in osteoporosis.

Data from the Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate trial showed a 41% reduction

in new x-ray-apparent vertebral fractures, and a 39% reduction in nonvertebral

fractures.[28] Risedronate also demonstrated a significant

reduction in hip fracture in a population of postmenopausal women aged 70 to

79 years.[29] Risedronate is also approved for the prevention and

treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in women and men. Risedronate

must be taken using the same regimen as alendronate: on an empty stomach with

a full glass of water, remaining upright, and waiting 30 minutes before having

any food or beverage.

Combination Therapy.

Studies have shown that increases in bone density with combination therapy

are greater than those achieved by either agent alone, but without additive

increases. Because there are no data regarding fracture reduction with

combination therapy, and no bone biopsy data, many bone specialists are

hesitant to recommend combination therapies until the data show greater

fracture reduction. However, if a patient who takes estrogen for menopausal

symptoms needs treatment for osteoporosis, most bone specialists will continue

her on estrogen therapy and add a bisphosphonate. It is currently not

advisable that estrogens and raloxifene be taken together; investigation is

underway.

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

Ongoing Studies

Risedronate is currently being evaluated to determine whether a once-weekly

dose is as effective as the 5-mg daily dose presently approved. A study of

nasal calcitonin is ongoing to determine the mechanism by which calcitonin

prevents fractures. A 5-year trial comparing alendronate with raloxifene

initiated enrollment in the fall of 2001. This is a very large study, with

primary endpoints including vertebral and nonvertebral fractures that will

give clinicians the first "head-to-head" comparison of the

antifracture efficacy and safety of a SERM and a bisphosphonate. This trial

may provide answers as to why, when compared to bisphosphonates in

postmenopausal women, raloxifene has produced similar vertebral fracture

reductions with small increases in BMD and small reductions in bone turnover.

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

What's Next?

In the near future, we hope to have anabolic therapies that will actually

increase bone formation. The first of these, parathyroid hormone, which may be

on the market within the year, demonstrated significant reduction in vertebral

fractures.[30] [Teriparatide therapy for osteoporosis was approved

by the FDA at the end of November 2002. The teriparatide package insert

includes a "black box" warning, acknowledging an increased risk of

osteosarcoma in rats treated with relatively high doses of teriparatide.

Treatment beyond 2 years is not currently recommended.] New SERMs are under

development, as are oral formulations of salmon calcitonin. Intravenous

bisphosphonates are also being evaluated for the treatment of osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

Conclusion

For now, our most effective means of treating osteoporosis remains

identifying patients, starting them on antiresorptive therapy, if appropriate,

and sending-them out into the world as "ambassadors for bone

health." Healthcare providers must also remember the basics: counseling

all patients to take adequate calcium and vitamin D, reviewing and encouraging

appropriate exercise activities, and discussing fall prevention. In addition,

clinicians must be mindful that hip protectors may be the most effective way

to prevent hip fractures in a given population.

Many postmenopausal women with existing osteoporotic fractures are not

diagnosed and treated. Only 22.9% of women with Colles fractures were treated

for osteoporosis in a large retrospective study of more than 3 million

patients in 30 states.[31]

Excellent therapies are available now, and it is hoped that better ones

will be available in the near future. With bone density studies, clinicians

have the tool to diagnose osteoporosis. By reviewing patients' charts, looking

for previous fracture, identifying a positive family history of the disease

and medications that could contribute to it, and examining patients for height

loss and kyphosis and other risk factors, clinicians can diagnose and treat

patients before a fracture occurs.

Osteoporosis: Fractures and Key Risk Factors

Robin K. Dore, MD

References

- Osteoporosis: both health organizations and individuals must act now to

avoid an impending epidemic. Press Release WHO/58. October 11, 1999.

Available at http://www.who.int/infpr-1999/en/pr99-58.html.

Accessed January 4, 2002.

- NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis

and Therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785-795. Available at http://consensus.nih.gov/cons/111/111_statement.htm#introduction.

Accessed January 4, 2002.

- Ducy P, Schinke T, Karsenty G. The osteoblast: a sophisticated

fibroblast under central surveillance. Science. 2000;289:1501-1504.

- Teitelbaum S. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:

1504-1508.

- Van Der Linden JC, Verhaar JA, Weinans H. Mechanical consequences of

bone loss in cancellous bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16: 457-465.

- Osteoporosis Overview. Fact Sheets. National Institutes of Health

Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases, National Resource Center.

Available at http://www.osteo.org/docs/30.464633275.html.

Accessed January 4, 2002.

- Kannus P, Parkkari J, Niemi S, et al. Prevention of hip fracture in

elderly people with use of a hip protector. N Engl J Med.

2000;343:1506-1513.

- Leech JA, Dulberg C, Kellie S, et al. Relationship of lung function to

severity of osteoporosis in women. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(1):68-71.

- Melton LJ. How many women have osteoporosis now? J Bone Miner Res.

1995;10:175-177.

- Schlaich C, Minne HW, Bruckner T, et al. Reduced pulmonary function in

patients with spinal osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int.

1998;8(3):261-267.

- Silverman SL. The clinical consequences of vertebral compression

fracture. Bone. 1992;13 Suppl (2): S27-S31.

- Cooper C. The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on

quality of life. Am J Med 1997; 103(2A):12S-17S.

- Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Population-based study of

survival after osteoporotic fractures. Am J Epidemiol.

1993;137(9):1001-1005.

- Kado DM, Browner WS, Palermo L, et al. Vertebral fractures and mortality

in older women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures

Research Group. Arch Int Med. 1999;159:1215-1229.

- Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC, et al. Risk of mortality following

clinical fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:556-561.

- Melton J. Vertebral fractures predict subsequent fractures. Osteoporos

Int. 1999;213-221.

- Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C, et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture

in the year following a fracture. JAMA. 2001;285(3):320-323.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Physician's Guide to Prevention and

Treatment of Osteoporosis, 1998. Available at: http://www.nof.org.

physguide.htm. Accessed January 11, 2002.

- Hannan MT, Felson DT, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Risk factors for

longitudinal bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham

Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:710-720.

- The Writing Group for the PEPI. Effects of hormone therapy on bone

mineral density: results from the postmenopausal estrogen/progestin

interventions (PEPI) trial. JAMA. 1996;276(17):1389-1396.

- The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Design of the Women's Health

Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials.

1998;19(1):61-109.

- Fontana A, Delmas PD. Clinical use of selective estrogen receptor

modulators. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001; 13(4):303-309.

- Johnston CC, Bjarnason NH, Cohen FJ, et al. Long-term effects of

raloxifene on bone mineral density, bone turnover, and serum lipid levels

in early postmenopausal women: three-year data from 2 double-blind,

randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Arch Intern Med.

2000;160(22):3444-3450.

- Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture

risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene:

results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. Multiple outcomes of

raloxifene evaluation (MORE) investigators. JAMA. 1999;282(7):637-645.

- Eastell R, Mallinak N, Weiss S, et al. Biological variability of serum

and urinary N-telopeptides of type I collagen in postmenopausal women. J

Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(1):522-529.

- Chestnut CH, Silverman S, Andriano K, et al. A randomized trial of nasal

spray salmon calcitonin in postmenopausal women with established

osteoporosis: the prevent recurrence of osteoporotic fractures study.

PROOF Study Group. Am J Med. 2000;109(4):267-276.

- Black DM, Thompson DE, Bauer DC, et al. Fracture risk reduction with

alendronate in women with osteoporosis: the Fracture Intervention Trial.

FIT Research Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85 (11):4118-4124.

- Harris ST, Watts, NJ, Genant HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment

on vertebral and on vertebral factures in women with postmenopausal

osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy with

Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282(14):1244-1252.

- McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the

risk of hip fracture in elderly women: Hip Intervention Program Study

Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344 (5):333-340.

- Neer R, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Recombinant human PTH (rhPTH

1-34] reduces the risk of spine and non-spine fractures in women with

postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344(19):1434-1441.

- Freedman KB, Kaplan FS, Bilker WB, et al. Treatment of osteoporosis: are

physicians missing an opportunity? J Bone Joint Surg Am.

2000;82A(8):1063-1070.

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

Introduction

The successful assessment and management of woman's cardiovascular health

after menopause is reliant on several factors.

Clinicians treating postmenopausal patients must be well versed on an

increasing number of cardiovascular disease (CVD) markers and risk factors.

The benefits and risks of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) must be weighed

with extreme care; familiarity with emerging therapies and new indications is

crucial for the optimal treatment of CVD in postmenopausal women.

This program outlines the important markers of CVD, with attention to

several new markers that likely are not familiar to most primary care

physicians and OB/GYNs. The role of HRT in cardioprotection is addressed,

based on findings from three major clinical trials of HRT in CVD.

Additionally, new recommendations recently issued by the American Heart

Association (AHA) concerning HRT use in CVD are summarized, as well as updated

guidelines for cholesterol testing and management from the third Adult

Treatment Panel (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP).

Finally, the roles of statins and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs)

in treating and preventing CVD are reviewed.

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

Markers of CVD Risk

Traditional.

The traditional markers of CVD risk in postmenopausal women include

elevated levels of low-density lipoproteins (LDL), low levels of high-density

lipoproteins (HDL), high triglycerides, family history of heart disease,

diabetes, hypertension, obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking. These

markers for CVD have been well established over many years and remain the most

important markers to emphasize to patients.

Novel.

In recent years, several new markers have been found that may prove

critical in the assessment of CVD risk. While not commonly used by the primary

care physician or OB/GYN, these markers are often used by cardiologists to

assess CVD risk in women who appear to be at high risk or have already

experienced a CVD-related event.

C-reactive protein: As a marker for systemic inflammation, C-reactive

protein (CRP) is considered an important component in determining the risk for

CVD. Researchers have known that CRP levels are higher in people with heart

disease, and they have long speculated that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory

process. With a simple but highly sensitive blood test that measures CRP

levels, the extent of underlying atherosclerosis can be determined and the

risk of future heart attack and stroke predicted. In a 3-year study of more

than 28,000 healthy postmenopausal women, CRP was the strongest single

predictor of future cardiac events, such as heart attacks.[1] Women

with the highest levels of CRP had a fivefold increase in the risk of

developing CVD and a sevenfold increase in the risk of having a heart attack

or stroke, compared with those who had the lowest levels of CRP. Levels of CRP

predicted these events even among apparently low-risk women, such as those who

did not smoke, had no evidence of high cholesterol, and had no family history

of heart disease. The investigators cautioned that standard laboratory tests

are not sufficient for determining CVD risk. Only high-sensitivity or

ultrasensitive tests for CRP are capable of predicting CVD risk.

Homocysteine: Elevated levels of this amino acid have been correlated with

artery damage, blood clotting, myocardial infarction, stroke, and other

manifestations of CVD. Inadequate intake of folic acid and B6 and B12 vitamins

is thought to cause increases in homocysteine. Plasma homocysteine levels

increase dramatically when a woman reaches menopause, and this is thought to

play a role in the increased incidence of vascular disease, cancer, and

possibly osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.[2,3] However, the

strength of the association between homocysteine and CVD is not certain, and

controversy exists about whether lowering homocysteine levels will reduce

Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) risk.

Fibrinogen: The body depends on this protein for proper blood clotting.

However, high levels of fibrinogen can restrict blood flow and lead to

hardened arteries and accumulation of plaque. Increased production of

fibrinogen is associated with traditional CVD risk factors (eg, obesity,

smoking, physical inactivity, diabetes).[4] Aging also has been

linked to high fibrinogen levels.[5] In healthy volunteers,

fibrinogen levels were markedly higher in those aged more than 50 years

compared with younger participants. Moreover, higher fibrinogen levels in

older adults corresponded with a 60% drop in dilation ability, whereas other

markers, such as HDL, LDL, and total cholesterol did not significantly

correlate with age or dilation ability. As such, the investigators noted that

fibrinogen is a highly predictive marker for reduced elasticity of the

endothelium.

Lipoprotein(a): Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is composed of an LDL-like particle

and apolipoprotein A. An elevated blood concentration of Lp(a) is associated

with an increased risk of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.[6]

However, Lp(a) is not considered as great a risk for CHD as are the

traditional risk factors. Moreover, measurement of Lp(a) is not standardized,

nor is it widely available in clinical practice. It has been suggested that

measurement of Lp(a) be reserved for those with a strong family history of

early CHD or with genetic predisposition to hypercholesterolemia, such as

familial hypercholesterolemia.[7,8]

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

The Role of HRT in CVD

Although HRT has an established role in the prevention of osteoporosis and

relief of vasomotor symptoms, controversy remains regarding the role of HRT in

CVD. Data from observational studies largely support the use of HRT in

postmenopausal women for a reduced risk of CVD; however, recent randomized,

controlled clinical trials have found no overall benefit of HRT in CVD risk

reduction or prevention.

The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) was the first

large-scale randomized trial of HRT for prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD)

in postmenopausal women.[9] After an average of 4.1 years of

follow-up, there was no overall benefit of HRT on secondary prevention of CHD.

In fact, during the first year of treatment, a significant (52%) increase in

cardiovascular events was noted in the HRT group compared with placebo. Fewer

events occurred as the study progressed, and benefit with HRT was seen by year

4. Based on these findings, the investigators recommended that HRT not be

started for secondary prevention of CHD. A 3-year follow-up study, HERS-II, is

currently underway to evaluate the longer term effects of HRT in secondary

prevention of CHD.[10]

In the Estrogen Replacement and Atherosclerosis (ERA) trial, no benefit was

seen after 3 years of treatment with HRT or with estrogen alone on the

progression of atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women with established

disease.[11] These results support those of HERS and consequently

lend more support to the recommendation that HRT not be initiated for

secondary prevention of CHD.

Several ongoing prospective angiographic trials should offer more insight

into the effect of HRT on the progression of coronary disease. Angiographic

endpoint trials include the Estrogen and Bypass Graft Atherosclerosis

Regression trial (EAGER), the Women's Lipid Lowering Heart Atherosclerosis

Trial (WELLHART), and the Women's Atherosclerosis Vitamin/Estrogen trial

(WAVE). In primary prevention, trials include the Women's Health Initiative (WHI;

of which the combination HRT arm has been discontinued as of July 2002) and

the Women's International Study of Long-Duration Oestrogen after Menopause

(WISDOM). In secondary prevention, trials include the Heart and Estrogen/progestin

Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II) and the Estrogen in the Prevention of

Reinfarction Trial (ESPRIT).[10]

One of these ongoing trials is the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), which

includes a large-scale randomized trial to assess the effects of HRT on

primary prevention of CHD over an 8- to 12-year period.[12] The

latest update from the WHI indicates an early increased risk of CVD events

among healthy women randomized to estrogen alone or HRT compared with placebo.

Fewer than 1% of women taking estrogen only or HRT experienced early CVD

events. Future updates are awaited for further information regarding the

long-term effects of estrogen or HRT on primary prevention of CVD.

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

New HRT Guidelines

An extensive analysis of the evidence from these current and ongoing

clinical trials led to the development of new guidelines by the AHA for the

role of HRT in CVD.[10] The new guidelines consider the use of HRT

in both secondary and primary prevention. In summary, the AHA recommends that

HRT not be initiated for the purpose of secondary prevention. This is based on

the lack of definitive evidence that HRT will prevent coronary events,

particularly among women with established coronary disease. For primary

prevention, the AHA states that decisive clinical recommendations for HRT use

must await the results of ongoing randomized clinical trials. However,

possible coronary benefits and risks can be factored into the treatment

decision for primary prevention.

The AHA emphasizes that the driving factor of whether HRT should be used in

primary prevention should be based mainly on established noncoronary benefits,

such as osteoporosis prevention, relief of vasomotor symptoms, and patient

preference. The decision to use HRT in secondary prevention should be driven

by noncoronary factors as well. For women who have an acute coronary event or

are immobile, the AHA suggests discontinuation of HRT.

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

Updated Cholesterol Management Guidelines

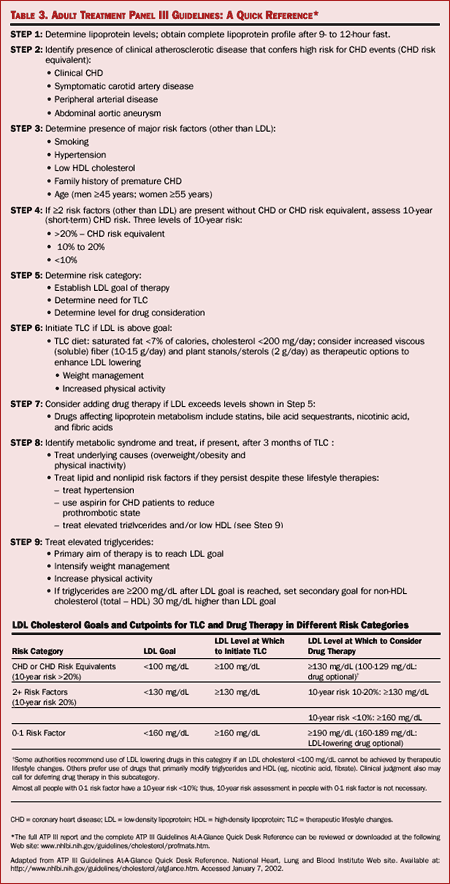

Clinicians should also be familiar with the Third Report of the NCEP Expert

Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in

Adults (ATP III).[13] This report, issued in 2001, describes in

great depth the NCEP updated clinical guidelines for cholesterol testing and

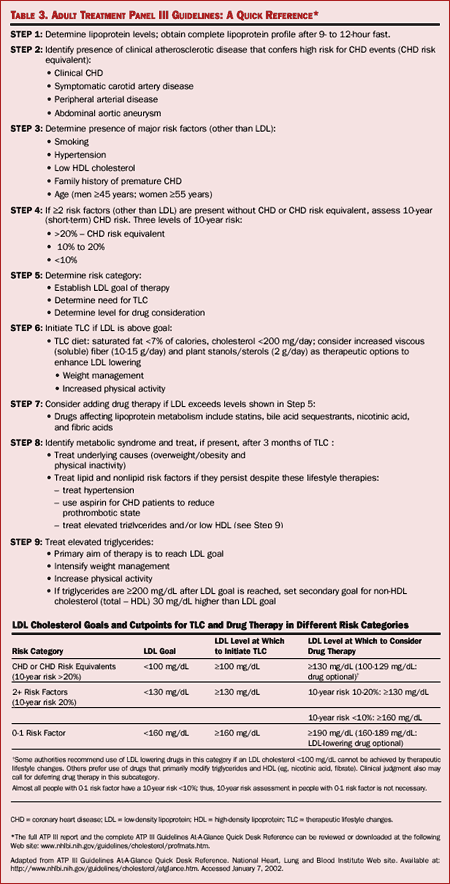

management. These guidelines are outlined in the table below.

Table. (click

to enlarge) Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines: A Quick Reference

The updated guidelines share many features with previous ATP

recommendations for the management of CVD in women with hypercholesterolemia,

but emphasize more aggressive lowering of elevated LDL levels. For example,

the ATP III guidelines recommend a target LDL of less than 100 in women who

have greater than a 20% 10-year risk for CHD. This includes women with

peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, abdominal aortic

aneurysms, or diabetes.

Another advancement in the ATP III guidelines is the classification of the

metabolic syndrome, a very common problem in postmenopausal women. By

definition, metabolic syndrome can be diagnosed in women with at least three

of the following factors: a waist circumference greater than 35 inches,

triglycerides at least 150 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol lower than 50 mg/dL, blood

pressure at least 130/85 mm Hg, or a fasting glucose at least 110 mg/dL.

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

Use of Statins and SERMs

Statins -- First-line therapy for CVD: Based on the AHA recommendations and

the ATP III guidelines, the general consensus for CVD prevention and

management in postmenopausal women is modification of lifestyle supplemented

with pharmacotherapy when indicated. Statins are currently considered the most

effective therapy for lowering LDL cholesterol levels.[14, 15]

Statins block the synthesis of cholesterol in the liver, which effects a

decrease in plasma LDL levels. These agents have been shown to dramatically

reduce levels of total serum cholesterol, thus demonstrating their beneficial

effect in reducing CHD events.[14] Studies among postmenopausal

women with hypercholesterolemia have reported that statins reduced LDL levels

by 25.4% to 45%.[15-20] Statins are also more effective than ERT/HRT

in reducing LDL levels,[16, 17, 19, 20] and have demonstrated

significant triglyceride-lowering effects compared with HRT.[20]

Thus, for women with elevated LDL cholesterol, statins are now considered

first-line therapy instead of ERT/HRT.

SERMs -- Emerging cardioprotective effects: SERMs are drugs with mixed

agonist/antagonist action on estrogen receptors in different tissues.

Raloxifene is a SERM indicated for both the prevention and treatment of

osteoporosis. Tamoxifen also belongs to the SERM class of drugs, and has been

shown to reduce the incidence of breast cancer in healthy women at high risk

of developing the disease. Studies of SERMs in CHD have shown that they are

capable of reducing LDL levels without affecting HDL or triglyceride levels

significantly in postmenopausal women.[21-25]

Studies in postmenopausal women also have demonstrated beneficial effects

of SERMs on several new markers of CVD. Both tamoxifen and raloxifene have

been shown to decrease levels of Lp(a),[23, 26] with tamoxifen

having a greater effect than that seen with conjugated equine estrogen.[26]

SERMs also have a greater ability to lower fibrinogen levels compared with HRT.[23,

27] In a recent study of tamoxifen, fibrinogen levels were reduced by

22%, and the drug was effective in reducing levels of CRP by 26%.[28]

These trials offer encouraging evidence for a potential role of SERMs in

CVD prevention; however, further research is needed to confirm the clinical

relevance of the beneficial effect on many markers of CVD. The Raloxifene Use

for the Heart (RUTH) Study is underway to examine more than 10,000

perimenopausal women for CVD and breast cancer.[29] Future

decisions regarding SERM use will likely be influenced by the effects of

compounds on more than one organ system.

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

Conclusion

Because CVD is the leading cause of death and an important cause of

disability in postmenopausal women, it is imperative that clinicians are

familiar with its emerging markers. It is also important that clinicians

understand all of the agents available to help women achieve lipid targets and

optimize risk-reducing strategies.

Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for Minimizing the Threat

Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

References

- Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and

other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease

in women. New Engl J Med. 2000;342: 836-843.

- Anker G, Lonning PE, Ueland PM, et al. Plasma levels of the atherogenic

amino acid homocysteine in postmenopausal women with breast cancer treated

with tamoxifen. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:365-368.

- Boers GH, Smals AG, Trijbels FJ, et al. Unique efficiency of methionine

metabolism in premenopausal women may protect against vascular disease in

the reproductive years. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1971-1976.

- Stec JJ, Silbershatz H, Tofler GH, et al. Association of fibrinogen with

cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham

Offspring Population. Circulation. 2000; 102:1634-1638.

- Allen JD, Wilson JB, Tulley RT, et al. Influence of age and normal

plasma fibrinogen levels on flow-mediated dilation in healthy adults. Am J

Cardiol. 2000; 86:703-705.

- Zenker G, Koltringer P, Bone G, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a strong

indicator for cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1986;17:942-945.

- Marcovina SM, Koschinsky ML. Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for

coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:57U-66U; discussion 86U.

- Marcovina SM, Hegele RA, Koschinsky ML. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary

heart disease risk. Curr Cardiol Rep. 1999;1:105-111.

- Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al, for the Heart and Estrogen/progestin

Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. Randomized trial of estrogen plus

progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in

postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1998; 280:605-613.

- Mosca L, Collins R, Herrington DM, et al. Hormone replacement therapy

and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from

the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001;104:499-503.

- Herrington DM, Reboussin DM, Brosnihan KB, et al. Effects of estrogen

replacement on the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis. N Engl

J Med. 2000;343:522-529.

- The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Design of the Women's Health

Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials.

1998;19:61-109.

- National Cholesterol Education Program. Third Report of the Expert Panel

on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in

Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). National Heart, Lung and Blood

Institute Web site. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/atp3_rpt.htm.

Accessed January 7, 2002.

- Gould AL, Rossouw JE, Santanello NC, et al. Cholesterol reduction yields

clinical benefit: impact of statin trials. Circulation. 1998;97:946-952.

- Gotto AM, Jr. Cholesterol management in theory and practice.

Circulation. 1997;96:4424-4430.

- Davidson MH, Testolin LM, Maki KC, et al. A comparison of estrogen

replacement, pravastatin, and combined treatment for the management of

hypercholesterolemia in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med.

1997;157:1186-1192.

- Herrington DM, Werbel BL, Riley WA, et al. Individual and combined

effects of estrogen/progestin therapy and lovastatin on lipids and

flow-mediated vasodilation in postmenopausal women with coronary artery

disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:2030-2037.

- Ushiroyama T, Ikeda A, Ueki M, Sugimoto O. Efficacy and short-term

effects of pravastatin, a potent inhibitor of HMG-Co A reductase, on

hypercholesterolemia in climacteric women. J Med. 1994;25:319-331.

- Darling GM, Johns JA, McCloud PI, Davis SR. Estrogen and progestin

compared with simvastatin for hypercholesterolemia in postmenopausal

women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:595-601.

- Sbarouni E, Kyriakides ZS, Kremastinos DT. The effect of hormone

replacement therapy alone and in combination with simvastatin on plasma

lipids of hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women with coronary artery

disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1244-1250.

- Love RR, Wiebe DA, Newcomb PA, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on

cardiovascular risk factors in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1991;

115:860-864.

- Love RR, Wiebe DA, Feyzi JM, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on

cardiovascular risk factors in postmenopausal women after 5 years of

treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1534-1539.

- Walsh BW, Kuller LH, Wild RA, et al. Effects of raloxifene on serum

lipids and coagulation factors in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA.

1998; 279:1445-1451.

- Draper MW, Flowers DE, Huster WJ, et al. A controlled trial of

raloxifene (LY139481) HCl: impact on bone turnover and serum lipid profile

in healthy postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:835-842.

- Delmas PD, Bjarnason NH, Mitlak BH, et al. Effects of raloxifene on bone

mineral density, serum cholesterol concentrations, and uterine endometrium

in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1641-1647.

- Shewmon DA, Stock JL, Rosen CJ, et al. Tamoxifen and estrogen lower

circulating lipoprotein(a) concentrations in healthy postmenopausal women.

Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:1586-1593.

- Grey AB, Stapleton JP, Evans MC, et al. The effect of the antiestrogen

tamoxifen on bone mineral density in normal late postmenopausal women. Am

J Med. 1995;99:636-641.

- Cushman M, Costantino JP, Tracy RP, et al. Tamoxifen and cardiac risk

factors in healthy women: suggestion of an anti-inflammatory effect.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:255-261.

- Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK, et al. Design and methods of the

Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) study. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:392-395.

The Faculty Speaks: A Roundtable Discussion on Postmenopausal Health Care

Thomas E. Nolan, MD, MBA; Susan Johnson, MD; Robin Dore, MD; Jane Cauley,

DrPH; Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

Cardiovascular Health

The following are excerpts from a closed roundtable discussion that took

place in October, 2001, entitled "HRT and SERMs: Evidence-Based Data to

Guide Patient Management." Dr Thomas E. Nolan acted as moderator.

As noted in "Cardiovascular Disease: New Recommendations for

Minimizing the Threat," by Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD, a great need exists

for education, screening, and intervention for cardiovascular illness in

postmenopausal patients.

Dr Nolan: When it comes to the prevention and management of cardiovascular

disease (CVD), for many years we've segregated male and female patients.

However, data are beginning to show that women have some of the same problems

with coronary arteries as men do. Also, many OB/GYNs are not well attuned to

the difference between primary and secondary prevention; in many cases, by the

time secondary prevention is needed, they have already lost control of that

patient.

Dr Johnson: What should be the approach in treating women who don't have

proven coronary heart disease but are at very high risk, because of such

conditions as diabetes and hyperlipidemia? Should we be giving them estrogen?

Dr Mosca: The question you are raising is one of risk equivalence. The

American Heart Association guidelines do not recommend estrogen for secondary

prevention. For nearly all postmenopausal women, there's some degree of

atherosclerosis. At some point, when it becomes clinically evident, we call

its management "secondary prevention." The problem with that way of

thinking is that the first time a woman manifests coronary heart disease, two

thirds of the time it's with sudden death. There are no prior symptoms. The

OB/GYN is in a unique position to treat women more aggressively and to not

wait until there is a diagnosis.

Even in women who are 55 or recently postmenopausal and have one or more

risk factors, I am aggressive in the prevention of CVD.

Dr Nolan: I try to intervene with patients early in menopause as well. I'm

not always successful, because patients are often not yet willing to accept

menopause-related interventions.

Pharmacotherapy.

Dr Mosca: As for hormone replacement therapy (HRT), it's generally not

being used now as a mechanism for the prevention of heart disease. In the

cardiovascular community, the data appear to be insufficient to use it when

there are many other methods [eg, physical activity, smoking cessation,

nutrition, lipid lowering via statin therapy, blood pressure medication] of

controlling CVD.

Dr Dore: What about primary versus secondary prevention and low dose

aspirin in women?

Dr Mosca: For secondary prevention, aspirin is well accepted. For primary

prevention, there's an ongoing trial right now. We do not generally recommend

aspirin in the setting of primary prevention.

Even though a benefit has been seen on an epidemiological level, mainly

among women with risk factors, aspirin therapy may increase risk of

hemorrhagic stroke.[1] Stroke accounts for nearly one third of all

cardiovascular events in women. Therefore, until we really have an evidence

base to suggest that aspirin lowers overall cardiovascular mortality, there

isn't a lot of enthusiasm to use it right now.

Dr Cauley: The Women's Health Initiative and the Heart and Estrogen

/Progesterone Replacement (HERS) studies both use conjugated equine estrogen (CEE)

and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). What about some of the other forms of

HRT? My understanding is that they're now being used more frequently.

Dr Mosca: The world literature still largely pertains to CEE and MPA. One

school of thought exists that different estrogens and progestins may exert

different cardiovascular effects. In particular, there is a lot of enthusiasm

in Europe over 17-beta estradiol. Last year, Hodis presented an estradiol

study showing a reduction in the progression of corroded intima-media

thickness.[2]

In terms of progestins, there is a lot of controversy surrounding whether

or not one progestin might be better than another. The literature is quite

mixed. The take-home message is that we don't know whether or not one form of

estrogen and/or progestin is better. It's worth pursuing these studies to see

if we can develop a database that qualifies for a larger-scale critical

outcome study.

Unfortunately, the long-term epidemiologic studies of secondary prevention

have been minimal. So, in this case, epidemiology data seem to be consistent

with the randomized trials. And there is no primary prevention outcome study

yet.

Depression and CVD.

Dr Nolan: I see a lot of symptomatic depression in postmenopausal women,

which is also a considerable risk factor.

Dr Mosca: Indeed. Although the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease

[ENRICHD] trial, the first major randomized, clinical trial to test treating

depression and low social support with psychosocial intervention, did not show

a reduction in cardiovascular endpoints, there was a statistical improvement

in depression and social isolation.[3] There is great opportunity

for us to make sure that women get appropriate treatment for these problems. I

suspect that depression, anxiety, and social isolation are major contributors

to CVD for women.

Dr Nolan: Our community is now really looking for depression and treating

it. Dr Johnson, you and I were talking about using selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for chronic pelvic pain and premenstrual

dysmorphic disorder several years ago.

Dr Johnson: Yes, and at present, a lot more practitioners are now

prescribing SSRIs for these and other hormone-related psychological mood

disorders.

Dr Dore: Thanks to the higher level of social acceptance than these agents

once had, patients as well as clinicians are now more willing to discuss and

use these therapies.

Dr Nolan: Indeed, and over the years, I'm finding less and less reluctance.

Twenty years ago, a colleague of mine said CVD was related to chronic stress

causing damage to the arterial walls. I thought it was an interesting theory,

and I still think there may be an element in there somewhere.

Dr Mosca: Absolutely. The role of psychosocial markers in CVD is now very

prominent. A number of studies have examined, for example, type A personality

as a risk factor for cardiovascular events. Unfortunately, most of this

research has been conducted in men. Only in recent years have even the major

studies begun to collect information about how personality traits and

reactions to environmental stress affect heart health. We all suspect that

these factors are major contributors to CVD in women.

Another issue is the multiplicity of the family and societal roles women

now have. For many years, women have been the caretakers of their spouse and

children; now, they are often also in the "sandwich role" of

caregiver for a parent, while also working outside the home. How the

psychosocial environment contributes to CVD remains to be determined. Common

sense tells us that it doesn't bode well to have competing priorities. Because

of these responsibilities, many women tell us that they don't have time to

exercise or to go to cardiac rehabilitation, for example. They feel their need

to care for others is greater than that to care for themselves.

When the World Trade Center disaster occurred, we set up a heart attack

prevention center downtown. We did it because severe emotional stress leads to

a host of responses from the body: Viscosity is increased, fibrinogen levels

are increased, blood pressure is increased, and cholesterol is even increased

in some studies. All of these markers can acutely affect risk among

individuals who have unstable plaque.

Here is another example: There tends to be about an eight fold increase in

the risk of cardiovascular events in the 2 weeks following earthquakes and

other natural disasters. For about 6 months, cardiovascular mortality rates

remain doubled.

Hormone Alternatives.

Dr Dore: Nutraceuticals are very important to my patients. Have any trials

looked at soy or red clover?

Dr Mosca: The soy data have been mixed, also. Some surrogate endpoint

studies, such as those on endothelial function, have been positive.[4]

Others have been neutral.[5] Many women like the idea of using a

natural form of estrogen rather than a pharmaceutical compound. I have

concerns about that, because I don't know exactly what they're getting or what

it's doing to their blood vessels. There's evidence that soy, when it's

replacing animal protein, can lower cholesterol.[4] Again, whether

these intermediate endpoint data are going to translate into beneficial

clinical outcomes remains to be determined. It would be very nice if we could

see a well-conducted trial of soy in postmenopausal women. In terms of our

recommendations, it's premature right now to say that soy has a cardiovascular

benefit.

The Faculty Speaks: A Roundtable Discussion on Postmenopausal Health Care

Thomas E. Nolan, MD, MBA; Susan Johnson, MD; Robin Dore, MD; Jane Cauley,

DrPH; Lori Mosca, MD, MPH, PhD

Bone Degeneration

Awareness is the key to preventing osteoporosis. Here, Robin Dore, MD,

author of "Osteoporosis: Focusing on Fracture and Key Risk Factors,"

discusses this disease with the other faculty

members, offering critical information on monitoring, prevention, and

treatment.

Dr Dore: My primary goal in speaking to patients and physicians is to

increase their awareness of osteoporosis prior to the fracture so we can

prevent those fractures from occurring. Luckily, we have many therapies for

preventing and/or treating these patients, including alendronate, raloxifene,

risedronate, and calcitonin. Estrogens no longer have the indication for the

treatment of osteoporosis as there has been no clinical evidence indicating

that estrogen reduces the risk of fractures. In the future, maybe next year,

we will have therapies that are anabolic and actually increase bone formation.

So what we can do today is identify the patients who are at risk, start them

on therapy, and have them be ambassadors of bone health.

We need to constantly emphasize to adolescents the importance of building

peak bone density -- through calcium intake, weightbearing exercise, and not

smoking.

Screening.

Dr Cauley: The National Osteoporosis Society guidelines do not recommend

follow-up bone mineral density (BMD) measurement once a woman is on therapy.

Why wouldn't you need them?

Dr Dore: The National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines on vertebral

fractures assume that the patient has osteoporosis. But a malignancy [eg,

multiple myeloma, primary malignancies of bone] can cause those vertebral

fractures as well. A patient could have a trauma as a child and not remember

having a vertebral fracture.

One of my patients had a vertebral compression fracture at T10. She was on

long-term thyroid replacement, had never taken estrogen, was at risk of

falling, and had a positive family history of osteoporosis. If I had treated

her, she would have taken therapy needlessly, because she had a normal BMD. As

it turns out, she had fallen down a flight of stairs when she was 12 -- that

was when the fracture occurred.

Dr Cauley: Bone mineral density is a good screening tool. It identifies

people at risk for fracture. But it's not perfect. A patient with a BMD higher

than -2.5 SD can still have a hip fracture.

Dr Dore: Indeed, the problem with the World Health Organization criteria

for osteoporosis is that age and prior fracture are not taken into account. I

put age first, fracture history second, and then T-score. So, if a person has

a T-score of -1.8 but has a hip fracture, I would certainly treat her. I

advise that these guidelines not be used too strictly.

Unfortunately, I've had many patients referred to me for treatment of

osteoporosis because they've had a fracture, and it turns out to be a

malignancy. I always evaluate a patient for malignancy if she's had a fracture

and the assumption has been that it's osteoporotic.

Dr Johnson: Do we know what the prevalence is of morphometric fractures in

women based on their BMD? For example, in women with BMD above -2.5 SD and who

are 70 years old?

Dr Dore: In 80-year-old patients, the prevalence is 44%.[6] With